RichardHerring.com

- Home

- Warming Up

- Gigs

- Sections

-

Shows

- RHLSTP Tour

- RHLSTP with Richard Herring

- Can I Have My Ball Back?

- Richard Herring - Oh Frig, I'm 50!

- Richard Herring - The Best

- Richard Herring - Happy Now?

- Richard Herring: Lord of the Dance Settee

- I Killed Rasputin

- Richard Herring's Meaning of Life

- We're All Going To Die

- Richard Herring's Edinburgh Fringe Podcast

- Talking Cock 2

- What Is Love Anyway?

- Christ On A Bike!

- Podcasts

-

Merchandise

-

DVDs

- Happy Now?

- We're All Going To Die

- Talking Cock (The Second Coming)

- 10

- What Is Love, Anyway?

- Christ on a Bike!

- Hitler Moustache

- The Headmaster's Son

- Oh Fuck, I'm Forty!

- ménage à un

- Someone Likes Yoghurt

- Twelve Tasks of Hercules Terrace

- Fist of Fun - Series 1

- Fist of Fun - Series 2

- Fist of Fun - Series 1 & 2

- Books

- Audio

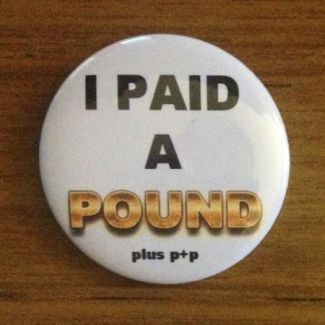

- Buy a Badge!

-

DVDs